Human capital collapse

Why the “Binary Outcome Industry" won’t be revolutionised overnight. Alternative title: AI-disabled meritocratic hierarchy in the age of Western industrial rebirth.

Note that I am posting in a personal capacity and this blog does not represent any positions of Relation.

With much interest in how Western economies have fallen behind, the question is how to rebuild capabilities across key industries: chip manufacturing, biotechnology, nuclear power, defence, and aerospace, to name a few. From the 1960s onward, the West built significant scaled operations in these areas, yet, by the late 1990s, we had systematically gutted these capabilities and, crucially, forgotten how we identified and trained people. The AI revolution has been heralded as a mechanism to both increase the quality and reduce the price of higher education, but AI cannot replace tacit knowledge; it does, however, radically reduce the cost of signalling expertise for technical roles. One might posit that we’re heading for disaster when you combine these trends with the capital-intensive nature of these “binary outcome industries” (BOI) where success is measured in a small number of critical events — a clinical trial readout, a factory commissioning, a rocket launch. From specialist mentoring to unwavering academic standards, there may be solutions to rebuild these BOI. However, doing so will require proactive decision-making by individuals, companies, universities and governments with the specific aim to preserve delivery capability as a national resource.

Here we discuss:

How do binary outcome industries operate?

Why do you hire someone for a BOI job?

How do we rebuild human capital?

How do BOI industries operate?

When you compare the “old industries” to new ones — technology, finance, consulting, and consumer — strange and nonlinear market dynamics reveal themselves. In pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, perfectly safe and efficacious drugs get abandoned for commercial reasons after hundreds of millions of dollars have been invested; nuclear power plants remain in various stages of completeness, spending decades in regulatory purgatory; and launch vehicles are lost in minutes after a decade of development. In contrast to the modern economy, these old industries require huge amounts of upfront investment. Less appreciated is that, akin to highly paid Silicon Valley software engineers, there is an extreme concentration of talent to deliver these mega-projects. A system of training courses and real-world assessments once identified singular leaders entrusted to lead the initiative of the day: from nuclear power plant builds and setting up factories to bringing a drug through clinical trials.

Consider the growth of the pharmaceutical industry. From the late 1800s to the mid-20th century, early pharma was a craft with many “drug hunters” travelling far and wide to harvest plants, fungi, and soil microbes to identify bioactive compounds, often leading to new antibiotics. Simultaneously, glands from various animals, and even humans, were being pulverised to find hormones with therapeutic action (see oxytocin, adrenaline etc). If one could isolate the active ingredient and scale its extraction, then one may have a flourishing business if the unit economics work. Key figures like Henry Wellcome developed the ability to judge what smelled promising, how to purify at multi-kilogram scales, and which impurities would hinder stability a year later. At this time, regulation was light and with clinical trials not mandated until 1962 in the USA (Kefauver-Harris Amendments), one could be commercially successful by merely shipping a product that didn’t obviously harm people.

As chemistry matured, so did patent strategy and regulatory pathways. Firms prioritised composition-of-matter claims and moved away from “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS) routes (formally introduced in 1958) because the most defensible commercial moat was exclusivity provided by patents and regulatory bodies (not just that you could manufacture the drug). With the Hatch–Waxman Act (1984), many “generics” companies selling off-patent drugs built internal groups to attack weak patents and gain an FDA protected 180 day market exclusivity. This meant that big pharma had to walk the line between filing IP early enough to deter “fast followers” (other drugs with the same mechanism) but late enough to cover ancillary aspects, such as formulation, delivery via medical device and manufacturing routes needed before launch, potentially followed by new use cases (“indication expansion”) — if discovered. This led to a professionalisation of regulatory science and executives became experts in reading the tea leaves of “what the FDA will actually accept”.

Eventually, molecular biology and human genetics created target-led discovery and, later, biologics and cell and gene modalities. If you believe the press, the future of health is all around precision medicine; the less appreciated story is around standardisation and integration of the discovery process itself. Various internal reviews became published highlighting factors predictive of regulatory and commercially successful drug launches (see AstraZeneca’s 5R’s framework, GSK’s work on genetic evidence for approved drug indications). This ultimately led to alignment in target validation standards, CMC tractability requirements, and the clinical contexts (patients, endpoints, standard of care) that regulators and payers will bless.

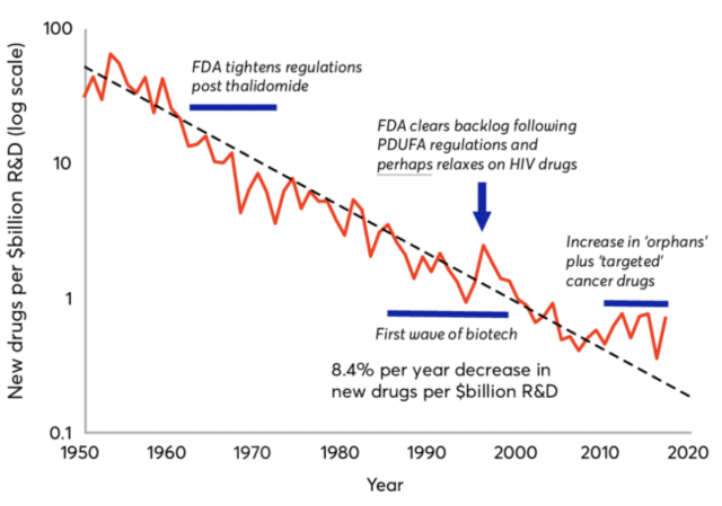

Zooming out, R&D spend per approval has risen over the past few decades even as tools improved, referred to as “Eroom’s Law” (Moore’s Law in reverse) with cost drivers including higher evidentiary bars, safety expectations in larger and longer trials, rare-disease fragmentation, and payer demands for comparators and real-world value. Each layer adds irreversibility: once you commit to tox species, a biologics expression system, or a pivotal endpoint, the project path is locked. That’s what makes pharma quintessentially a BOI: a few irreversible choices compound toward one or two binary events.

Moreover, beyond the cash-intensive R&D process itself with revenue generation pushed a decade into the future, valuations jump discontinuously on data. For biotech, this creates pressure to treat interim analyses and regulatory interactions as pieces of an equity story; and for big pharma, these discontinuities allow for dynamic reallocation of capital across their pipeline as programmes get killed whilst new ones get formed, either organically, or via mergers and acquisitions.

To manage this process, big pharma historically invested in leadership finishing schools: executive development programs, mock FDA meetings, media/comms training, crisis simulations, and rotations across departments and functions. The output was a small cadre trusted to manage $100M+ assets from pre-IND to launch. Their edge was knowing who to call out of hours when your fill-finish yields crash (final manufacturing step); which vendors never hit timelines; and how to negotiate a Special Protocol Assessment without boxing yourself in (a specific FDA meeting).

As we see above, critical events define huge value generation for stockholders. Remarkably, this is not how most modern businesses operate: someone, often young, builds a minimum viable product, generates small amounts of revenue, demonstrates this de-risked concept to investors, and then external capital scales the operation to make millions, if not billions, of dollars (see Meta, Twitter, Instagram, etc). BOIs look nothing like them.

Hiring for BOIs

Why do you hire someone?

At a very high level, a company has work that needs to be done beyond the current available headcount. After posting a job advert, one needs to evaluate applicants based on skills, accomplishments, and some kind of cultural fit; candidates get benchmarked against a role spec before an offer is made. What is less explicit is that experienced hires also get judged on tacit knowledge (alluded to above), and junior hires get judged on potential — basically, can you show that you’re smart?

What is tacit knowledge and why is it so important?

Tacit knowledge is the unwritten ways of working to deliver these outcomes, earned through hands-on experience and overhearing the conversations that one would not wish to speak too loudly. For a small example, in my past blogpost, I stated how AI-generated molecules are often far more expensive than using a traditional CRO, which breaks most of the VC narratives that TechBio companies are cheaper than the alternative — arguably diminishing the value proposition of their portfolio companies. Often, when someone is being interviewed for a senior position, they are subtly (or not so subtly) hinting at the tacit knowledge they have accumulated.

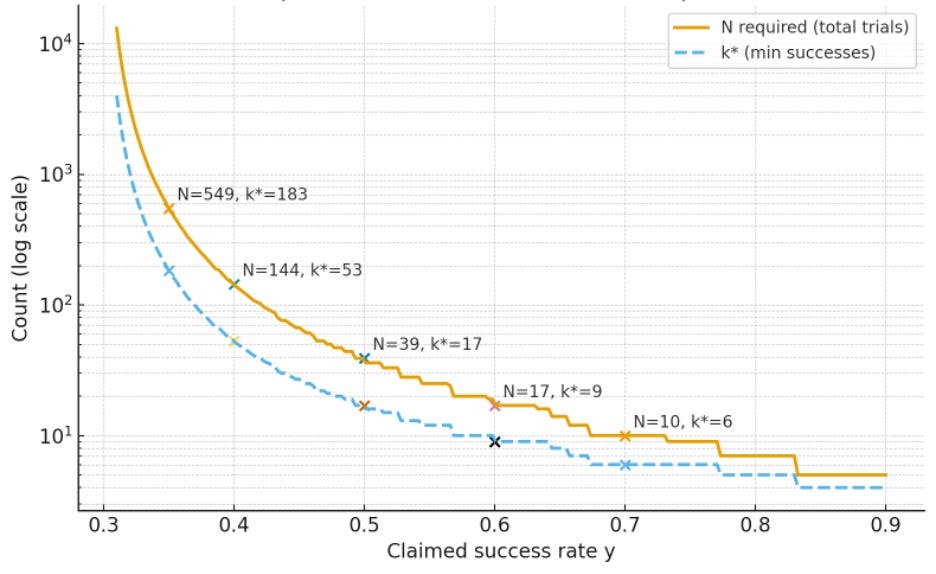

The other challenge with tacit knowledge in BOI is that it’s really hard to measure. Consider that the rate of success for a Phase 2 clinical trial for efficacy is approximately 30%. Suppose we wanted to assess whether an industry leader with presumed expertise (that improves clinical trial outcomes) was better than average at bringing drugs to market.

Let p = 30% denote the market baseline and let the leader claim a success rate y. If we model each trial as an independent Bernoulli outcome with success probability p. We can then ask: how many successful trials, k, out of how many total trials, N, one would have to had run, such that y>p with 95% one-sided confidence and 80% power, i.e., that they are better than the market.

As you can intuit, you must run 100s of clinical trials to detect small improvements over the market, illustrating why performance is hard to validate statistically in BOI. The larger differences are easier to detect. However, with all of the complexities in bringing a drug through clinical trials and all of the different stakeholders involved — is it even meaningful if a decision maker claims that are reliably be 2x to 3x better than the market? Realistically, if an executive has run over a dozen phase 2 trials, this is already quite a singular person towards the end of their career.

How do you know if someone is smart? Can you prove you’re good at what you do?

When looking at junior hires for a BOI, with or without a PhD, you are looking for evidence of logical and agile thinking under pressure, social grace, and ideally some signs that they have a level of conscientiousness and experience that their compatriots did not: managing a university club, strong academics, personal projects, or even writing a paper relating to original research. While the prestige was diminishing for all the above, AI has now well and truly undercut all meaningful ways a student used to stand out.

At the undergrad level within the Ivy League and liberal arts colleges alike, the prestige of setting up or running a social club is increasingly being treated as a résumé booster or a way to meet influential after-dinner speakers — often at the cost of genuine passion for a subject. From a testing perspective, universities have long been chastised for declining standards; for example, both Harvard and Yale reported that 79% of grades were in the A range in 2020–21 and 2022–23 respectively1.

At the graduate level, the recent step change is that AI can even write semi-convincing, and perhaps even convincing and correct, research papers — too much for any journal or conference to accommodate and gatekeeping has scaled accordingly. Historically, the main recipient of high-volume research articles were the pure mathematics journals: there was a certain romanticism that appealed to the amateur mathematician of being the next Ramanujan and finding a proof to a Millennium Prize problem. The journals generally took a pragmatic, if exclusionary, approach: blanket reject any submission without institutional backing or appropriate recommendation.

With the rise of newly formed non-research-intensive Asian and African universities, and the general growth of paper mills and low-quality venues, low-quality scientific work started seeping into the mainstream, purporting results that could not possibly be true. Retractions have surged: more than 10,000 research papers were retracted in 2023 across publishers; in 2024, Springer Nature alone retracted 2,923 papers. The established journals had to follow suit by more aggressive triage — pre-screening investigators through informal “Meet the Editor” webinars and assistant-editor checks before peer review.

Finally, the ML and AI conferences known for their rapid publication culture may now be at breaking point. NeurIPS 2025 received over 21,000 submissions in total and accepted ~25% in the main track (in previous years ~5.5% of submissions were flagged for ethics review). By submitting a manuscript, you also agree to review a handful of other manuscripts (the only way one could organise such an event). At that scale, even well-intentioned processes strain: heterogeneous reviewer quality paired with limited venue capacity has led to frequent overruling of decisions weakening the link between reviewer mark and acceptance of the work.

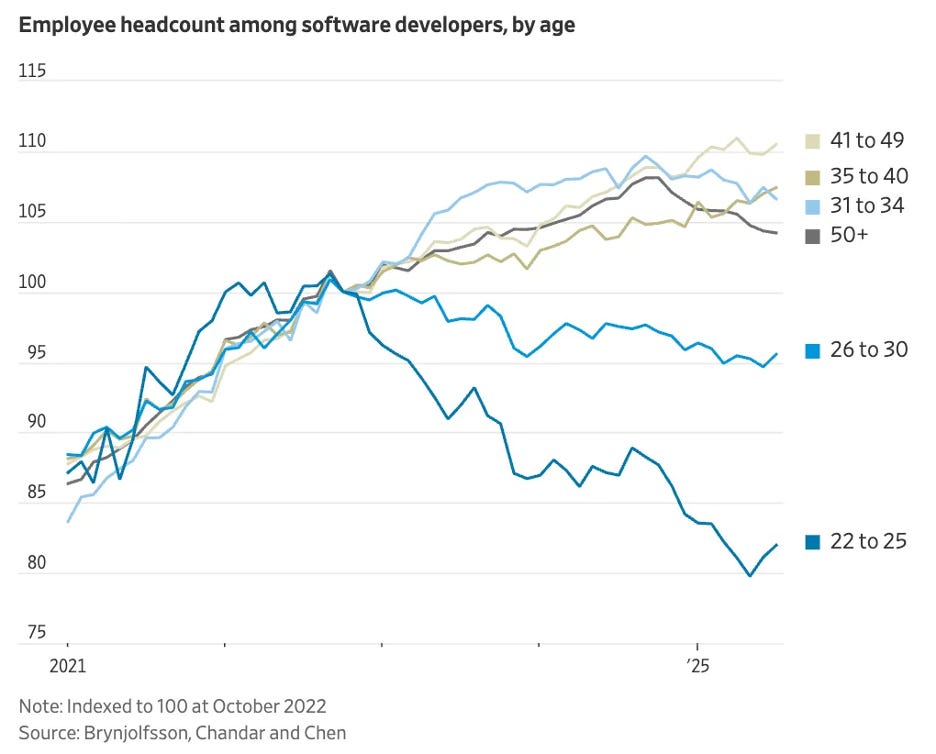

The power of AI is not imagined and is clear that for those without track records, the number of job postings is drying up.

The system for identifying talent worked when elites could find other ways to distinguish themselves. Unfortunately, now there’s a smaller and smaller aperture to definitively say “this person is smart because they did A, B, C”. AI reduces the dynamic range for signalling talent — which is an even bigger problem for BOIs, where performance is revealed only at a few binary events.

How do we rebuild human capital?

For individuals: Seek mentorship (especially across disciplines and departments) and avoid full-time WFH, you want to essentially build an understanding of the value chain that your business operates in so to understand how and why decisions are made. Most mentorship that people seek out defaults to prestige matching (titles, brands), but may not actually provide any meaningful insight into how business gets done.

For companies: Startups should hire senior operators early for tacit knowledge before irreversibility locks in — hugely important as your burn rate ramps up as you will only get a few shots on goal. In many BOI settings, this is a well trodden path, see Space X (Shotwell, Koenigsmann), TSMC’s founding team included Morris Chang, John C. Martin was seen as pivotal for Gilead --- and Relation are trying something similar2. We need to institutionalise apprenticeship. Finally, we could have a golden age for recruiters and hiring teams as they will be needed more than ever to do much more in person assessments when compared to online tests.

For conferences: Introduce submission fees, require code/data disclosure or registered protocols where applicable to increase the cost of false signalling.

For universities: Stop computational assessments (obviously) and return to unwavering academic standards by re-emphasising closed-book and oral exams3, so the cognitive burden is not solely on businesses as to work out when to hire someone.

For governments: Offer tax benefits and create programmes for retired executives to help and advise start-ups and growth stage companies. We need mechanisms of transferring tacit knowledge.

But don’t forget. Eventually, the old BOI industries will reinvent themselves to be industries of the future. Artificial intelligence, genomics, and nuclear fusion are going to be a young person’s game. There are always distinct differences between people who grew up living a topic and people who learnt later. You can’t fake intuition, so let’s build systems that build it.

With the growing privatisation of universities whereby the student is the “customer”, there are natural adverse incentives to increase customer satisfaction.

We at Relation thought about senior talent far earlier than most, from the leadership team, including our CEO, CTO, SVP and VP positions are all filled by big pharma alum, along with many others within our ranks. This has benefits far beyond just knowing how to operate, they have unique insights on along the value chain.

If you need a short-cut to hiring someone technical, just focus on the top Swiss universities. They’re known for rigorous first-year attrition in STEM (sometimes in the ~80% region), so you barely need to ask for a technical interview.