The economic rationale for biomolecular foundation models

Why some are much more valuable than the others; a brief note

Before I begin, note that I am posting in a personal capacity and this blog does not represent any positions of Relation. However, it does somewhat include reflections I’ve made from conversation with my talented colleagues!

In 2021, a who’s who of academics at Stanford popularised the term “foundation model”, exclaiming how by sinking millions of dollars into training runs, one could achieve vast out of distribution generalization capability. Across a range of industries, these models have boasted a range of use cases, from audio and vision generation to robotics and automation. Counter claims have however haunted the term: first, does it make sense to spend so much money? Second, providing such expenditure makes sense, can one achieve similar results at a fraction of the cost?

One field I’m most familiar with has been biomedical research. Below, I give my take on what does (and doesn’t) make sense at the biomolecular level.

Protein foundation models

In 2021 DeepMind dropped AlphaFold2, and triggered by this, a slew of “AlphaFold-for-X” companies were formed and funded, each with their own vaguely interesting twist. From antibodies to peptides, gene or cell therapies, every therapeutic modality under the sun had a Techbio startup1 waiting to sell you a story: the reason said modality never achieved commercial success was that an expensive, crack AI team wasn't available to steer the ship.

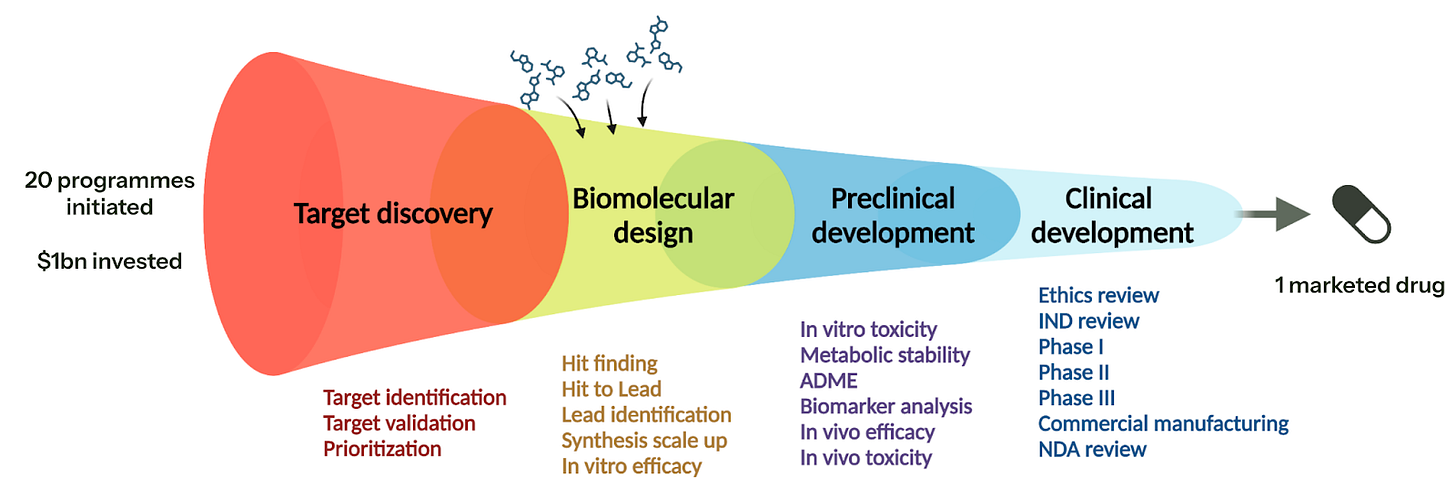

Unfortunately, the one thing many VCs forgot to check was the unit economics: essentially when you hire a team of ML researchers and engineers, you need to benchmark the strategy to the traditional way of doing things. By and large, when you compare the hundreds of millions of dollars required to bring a drug to market, spending low single-digit millions with a CRO to make a molecule for your target is an acceptable price to pay. However, the cost-benefit analysis of adding an ML research team and associated compute into the mix has yet to be elucidated… very long term, perhaps you can drive down the timeline (or even cost) of biomolecular design, but short term you are bankrolling platform creation of unclear value.

To be clear, I am specifically referring to performing ML research with large compute requirements in a company setting. As Charlotte Deane laid out in her talk at AIxBIO, published models are already an incredibly useful support tool, but (IMO) the economic argument in performing research in the area outside of academia is limited. Essentially, the models are competing over very small performance gains — gains that do not necessarily translate into real world value. Whilst I could dig out results from a survey paper and try to translate test set performance into a real world consequence, a more pertinent anecdote is that when we have been provided costs by a number of providers to a initiate a small molecule discovery campaign: the AI-enhanced companies came in at a ~3x multiple. Unfortunately, the multiple is not justified: there is no compelling data pack to date that demonstrates superiority over a skilled medical chemist.

With this in mind, it is why it’s slightly disappointing to see that 4 years later, the UK government didn’t get the memo and is funding a new protein-ligand database (~£8M for 500k structures) explicitly as part of an AI-driven drug discovery strategy2. On one hand, I’m really pleased to see the government lean into the sector. On the other hand, £8M is trivially fundable a pharmaceutical company if they felt this dataset would move the needle. Moreover, every retrospective analysis and commentary of why clinical trials fail (the largest cost in clinical development) tells us that lack of efficacy (and also safety) is the main reason for clinical trial failure, i.e., we didn’t understand the underlying biology3. One of the few reproducible signals that are predictive of clinical success is as to whether the drug target in question is linked to the genetics of the underlying disorder (Nelson 2015, Nelson 2024).

To summarise, I do not think the numbers add up — at least for small molecules. Moreover, I don’t think that designing biologics will change the paradigm a huge amount without clear forethought on what the use case is. For example, we can generate millions of candidate antibodies through a range of display methods, so merely optimising for binding isn’t differentiating; other properties pertaining to practicality and scale up may make more sense. Finally, companies like Dyno Therapeutics seem to be bucking the trend by bringing together structural models with an experimental platform to screen capsids for gene delivery — an area that has historically been challenging to optimize — everything ends up in the liver!

DNA foundation models

Contrast this to DNA foundation models: typically we are trying to learn the relationship between novel genetic variants and the downstream regulatory consequences within a certain window (say, up to ~1M base pairs). In fact, this is really two problems in one: when a genetic variant falls within a coding region of a protein (called an exon) and the mutation causes a change in the protein’s amino acid sequence, then we obtain an altered structure (perhaps providing greater justification for protein foundation models). However, approximately ~90% of variants found in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are non-coding.

When a genetic variant is in a noncoding region, we see changes in how DNA is transcribed into RNA. This is a tricky problem as DNA is wound around histones and densely packed within a cell’s nucleus, generating complex nonlocal relationships that we wish to learn. We achieve this by feeding a transformer-style deep learning model genetics with other genomic modalities, say RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, or ChIP-seq etc. Ultimately, if you can learn the relationship between arbitrary DNA sequences and downstream gene expression, then you have the means to identify new drug targets4. For example, if overexpression of a gene causes a deleterious phenotype, one can design a drug to inhibit the function of the corresponding protein.

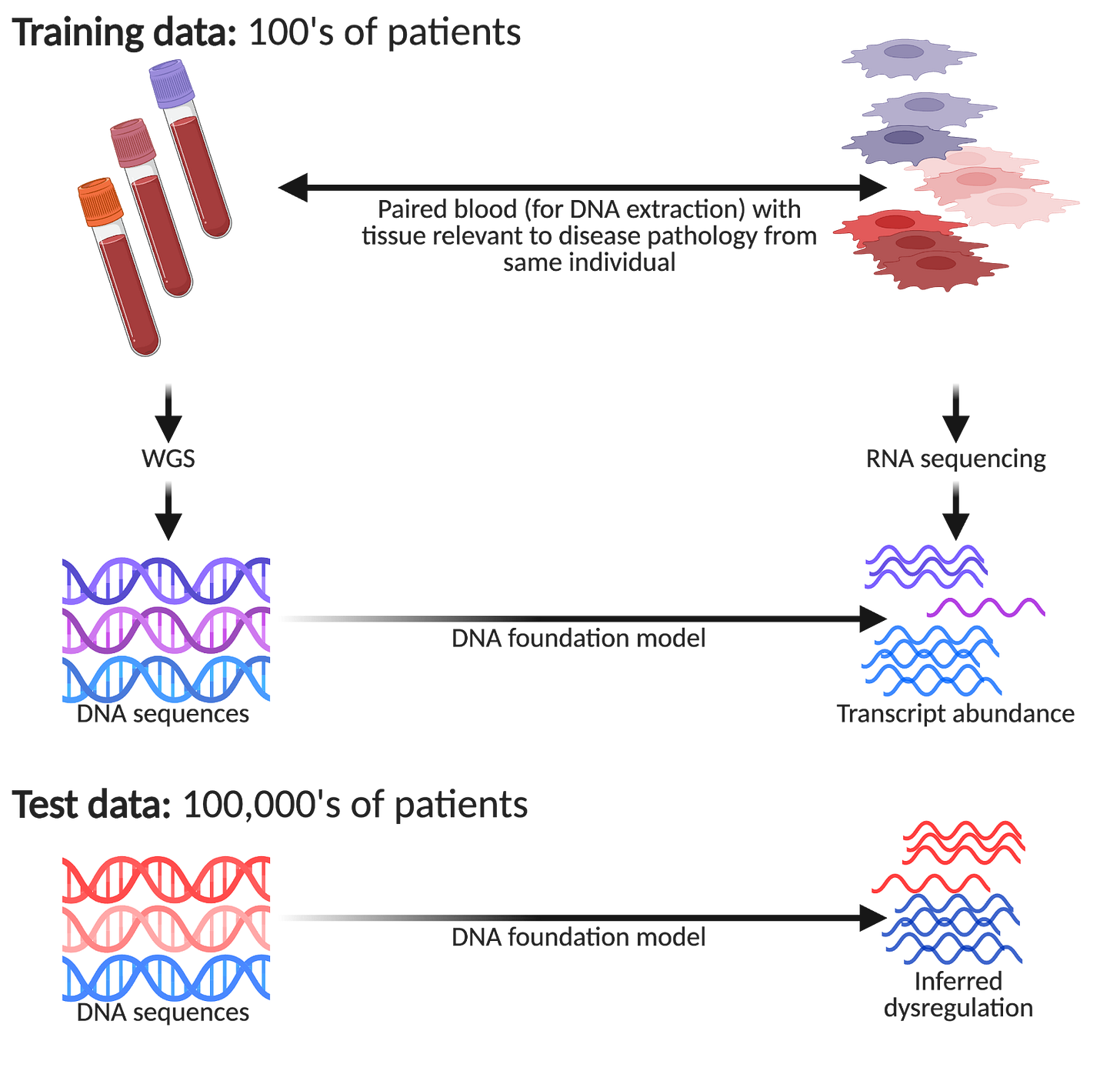

One aspect people seldom factor into their reasoning of why DNA foundation models are so interesting is how they can hypothetically reduce cost, labour, and practicality constraints of performing tissue profiling at scale. Imagine you decide to run a study to collect paired genetics with single-cell profiling of some tissue of interest. You need to pay for sample acquisition (e.g., patient fees, hospital fees, couriers), sample preparation (e.g., tissue dissociation, an appropriate single-cell technology), and sequencing. Fraught with logistical challenges, you will also need a capable and experienced lab that is frequently on call to receive samples! It goes without saying, this is a very expensive endeavour.

However, imagine you have an AI team that built a DNA foundation model trained on the data you have generated (say ~100 patients or so), you can now make inferences on much larger groups of patients, courtesy of large national biobanks. For example, the UK Biobank has ~500,000 volunteers, All of Us are aiming for ~1,000,000, and Our Future Health is aiming for ~5,000,000! Within such biobanks, we have patients presenting different disease pathologies donating their DNA, but seldom with the associated disease tissue of interest collected. This is a huge opportunity to detect subtle differences in how genetic variation manifests itself in large patient cohorts that would be undetectable in the original small patient group.

Regardless of how much VC capital has been raised, one cannot perform single-cell profiling on hundreds of thousands of patients!5 Remarkably, one unique property of using DNA foundation models in such a way is: if you increase model performance, one may be able to make more nuanced inferences with smaller patient numbers. So theoretically, improving benchmarked performance can translate to valuable real world gains (justifying investment).

“Virtual cell” foundation models

A new term has gained popularity, the “virtual cell”, encompassing a range of foundation models largely trained on single-cell perturbation data. Ironically, these models are not at all virtual cells (in the sense that we are simulating molecular dynamics), but for ease of reading, I will reluctantly continue using the term. At a high level their goal appears to be simple: to predict the effect of unseen perturbation on a gene expression profile. However, there are several much deeper (more valuable) problems related to this:

1. If you can link predicted gene expression (or some other dynamic ‘omic readout) to functional phenotypes you actually care about (e.g., T cell exhaustion, cancer growth etc), then one has a mechanism to propose new drug targets off the back of this.

2. If the interventional data generated can be faithfully mapped to observational human biology in situ, one may be able to find drug targets that transform a diseased state into a healthy one.

3. If one has an exquisite time-resolved understanding of gene expression dynamics, then one can definitively say what the causal chain of events was leading to the emergence of phenotype of interest. This is very important if you want to understand the potential for on-target toxicity effects.

4. Finally, depending on the out of distribution performance of the model, one may be able to perform transfer learning between cell types, or even say something about multicellularity, advanced model systems, and emergent phenotypes.

If you can do (1-4), then you have an exceptionally valuable platform — it is akin to dropping both target discovery and potentially other elements of preclinical development in the diagram below:

However, there is one key problem: there is nowhere near sufficient data in the public domain to do this properly. If analysis of recent press releases are anything to go by, there is an excessive focus on having a very large headline number of cells sequenced — not paired phenotypes or a clear focus on specific disease areas6. Naturally, I’m very interested to fix these problems, but I will save the end of this analysis for future post.

As I know a bunch of these founders (and they’re great people), I’m not going name specific companies.

Relation’s CTO Lindsay Edwards has a great line when evaluating AI use cases: “by the time you’re collected that much data, do you even need the model anymore?”.

At Relation, we perform single cell profiling of bone, which is especially interesting for two reasons. First, it’s a notoriously difficult sample type to work on; but second, as it would be horrifically unethical to randomly mandate that millions of people must have a joint replacement surgery, you actually cannot run an (unbiased) study across the general population.

This tweet erroneously got a lot of attention… the best 1-line takedown is here.

VCs always ready to bankroll the next shiny penny.

I’m starting to think that if we can define what kinds of data are needed to build better models maybe we need to develop different technologies and tools to do the millions of patients x millions of cells experiments.