Towards radical simplification

The UK’s runaway complexity needs a reset before we can expect meaningful growth

Before we begin, note that we are posting in a personal capacity and do not in any way reflect the views of our employers. Moreover, this piece is not meant to advocate for any partisan position. We also hope that this is not received as a bog standard “deregulate” piece, but about how we design effective policies from the outset.

Jake originally started this work in 2024 and as such it is written in the first person; Michael got involved to provide some much needed historical perspective and runs a specialist consultancy in the area.

Motivation

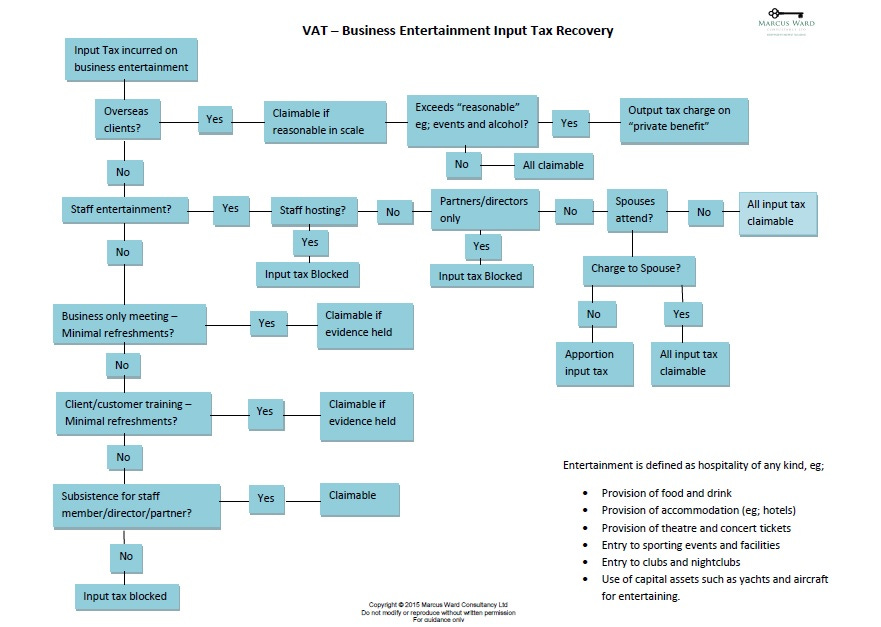

Here’s a pretty harmless example: have you ever wondered whether you can claim VAT back on entertainment expenses? Thankfully, a consultant has provided a rather definitive flowchat (below, from 2017), but it begs the question: why on earth is the system for something so trivial so complex? If you were to start from scratch, no one sensible would design such a policy.

When everyday interactions induce such friction, what are the economic costs to such complexifying triviality at a societal level? Could this be part of the explanation for why the UK economy is flatlining?

Observations

Consider the following:

From trains to nuclear power plants, all major infrastructure projects appear to be hopelessly slow, overbudget, and uncompetitive when compared to European peers.

Despite having a single national healthcare provider, the UK was unable to build a cost-effective (or even, effective) COVID-19 tracking system.

The UK has the 2nd largest HR sector globally (normalised against population size).

Less than <5% of projects by the Ministry of Defence were given a “green” rating by the National Audit Office, with all remaining projects labelled with serious shortcomings or as “unachievable”.

In spite of the UK’s global reputation in STEM prowess, our premier AI research institution appears to have been largely irrelevant in the face of modern deep learning advances, especially Large Language Models.

The UK appears unable to jail violent repeat offenders, with various loopholes often attributed to disappointing jail terms and conviction rates.

Below, we give thoughts on:

The current situation: why we are here and what we should be aiming for.

Challenges with radical reform and what we can learn from them.

How should one design a system from scratch with policy examples.

What is unique about the UK, when compared to the world at large.

Theory

The way we, British, live our lives is governed by case law, leading to rules, regulations and customs slowly accumulating over generations. As the empire expanded, the United Kingdom thrived from subjects building significant fortunes overseas, before eventually returning home and encouraging the adoption of laws to protect their new-found wealth. The world economy has changed, soon to be transformed further by AI, and Britain is struggling to navigate this new globalist age; she is without an empire but with the legal and regulatory baggage of a bygone era.

In recent decades, many former colonial states have overhauled historical laws and constitutions with impressive results (e.g., Hong Kong). Whilst many analyses have highlighted cultural factors, I argue that simplification is key — not only the bureaucratic process in and of itself, but crucially the underlying principle, policy position, and mechanism should be simple. In short, simplicity is transparent and if set up correctly — hard to exploit whilst motivating productive behaviour. A frictionless experience of everyday life should be the goal of a globally competitive Britain and one I advocate for below.

The British Policy Landscape: A Maze of Complexity

After reading Foundations, an idea solidified: UK government policies and administrative processes are bogged down by two intertwined problems. First, we have myriad specific “if-then” code blocks that are vaguely understandable (and you find glimpses of them on government websites). But second, we also allow for discretion and extenuating circumstances to be considered.1 This affects all political persuasions and inconveniences every socio-economic group.

Here are two everyday examples. First, consider how your personal tax bill is calculated: income tax is banded based on earnings; capital gains have a fixed rate; if you buy a house, you pay stamp duty etc. However, all these forms of tax have various exemptions and rebates (marriage, children etc). The logical conclusion to this is that past a certain point, people (and companies) inevitably engage with accountants and lawyers to reclassify one form of income as another to minimise their tax bill.

Second, imagine a homeless person attempting to access housing. This task is apparently so complex that the leading UK homelessness charity, Shelter, primarily provides advice on how to get housing from the government — not providing it themselves. Our desire to algorithmically classify the relative severity and neediness of our most disadvantaged also leads to perverse outcomes: incentives now exist to misrepresent one's personal circumstances to game the system.

This all becomes hugely wasteful: too many of our most gifted and able members of society build expensive esoteric expertise for hire so that others may effectively navigate daily life.2 3

The Power of Simplicity

When pitching to potential investors or collaborators, I’ve always been (strongly) advised that any core idea should be encapsulated in a single, clear sentence. As a mathematician and scientist, I found this extremely challenging; after all, every idea demands context, scale, and nuance. Yet, the ability to distill complex ideas into a single, resonant statement demonstrates clarity and vision.

This principle of simplicity has proven to be a major force behind some of the world’s most successful companies. Consider Apple; Steve Jobs’ relentless pursuit of simplicity created products so intuitive that even toddlers and seniors can operate them after minimal instruction. This isn’t just about consumer electronics; it’s a principle that applies to the broader economy. By stripping away unnecessary complexity, we can create systems that are both accessible and robust.

The British state is in drastic need of simplification, but why is it complex in the first place?

Elites lobby for complexity — hindering economic growth

In “The Rise and Decline of Nations”, Mancur Olson warns that when small, well-organized interest groups gain power, they steer government policy to serve their narrow benefits — even if that means layering on complexity that ultimately stifles progress. For example, in pre-revolutionary France, a patchwork of feudal dues placed heavy burdens on peasants while enriching the nobility: tenants had to surrender a portion of their harvest (champart) and were forced to use the lord’s facilities (banalités), such as his mill or oven, creating an opaque and exploitative system that hamstrung agricultural innovation and deepened rural hardship. The French Revolution dramatically transformed this legal landscape with the National Assembly abolishing the feudal system via the August Decrees (1789), canceling personal servitude and most feudal dues (with complete cancellation by 1793). The natural conclusion drawn is that revolutions reset such adverse policies.

Within “The Shock Doctrine”, Naomi Klein expands this point and details how deadly events like wars, revolutions and natural disasters can quickly lead to major shifts in corporate ownership, organizational structures, and political philosophies — in particular, highlighting free market economics. Regardless of whether you believe such revolutionary moments shift the political compass left or right, they do allow for such nonlinear shifts to occur. Peaceful, painless and well-functioning examples of transformation involving zero fatalities are regrettably hard to come by. It should go without saying that revolutions are not desirable,4 however finding ways to “reset” key aspects of British policy is becoming hugely necessary. It also somewhat goes without saying that Britain hasn’t had a revolution in quite some time (1651), so now we discuss lessons from history.

Undoing complexity: qualities of successful change management

If we are conceptually happy that complexity ferments over time, then what impact does this have on state capacity? Can one execute on major infrastructure projects? Finally, what do attempts of reforming runaway complexity look like?

Change management literature argues that project leaders focus too much on project design, and less on project implementation. As Kennie and Middlehurst called it, the most common approach is the ‘”Tsunami”: everybody involved, massive communication, then hope’. There is clearly a gap between expectations and reality, even when the stakes are high.

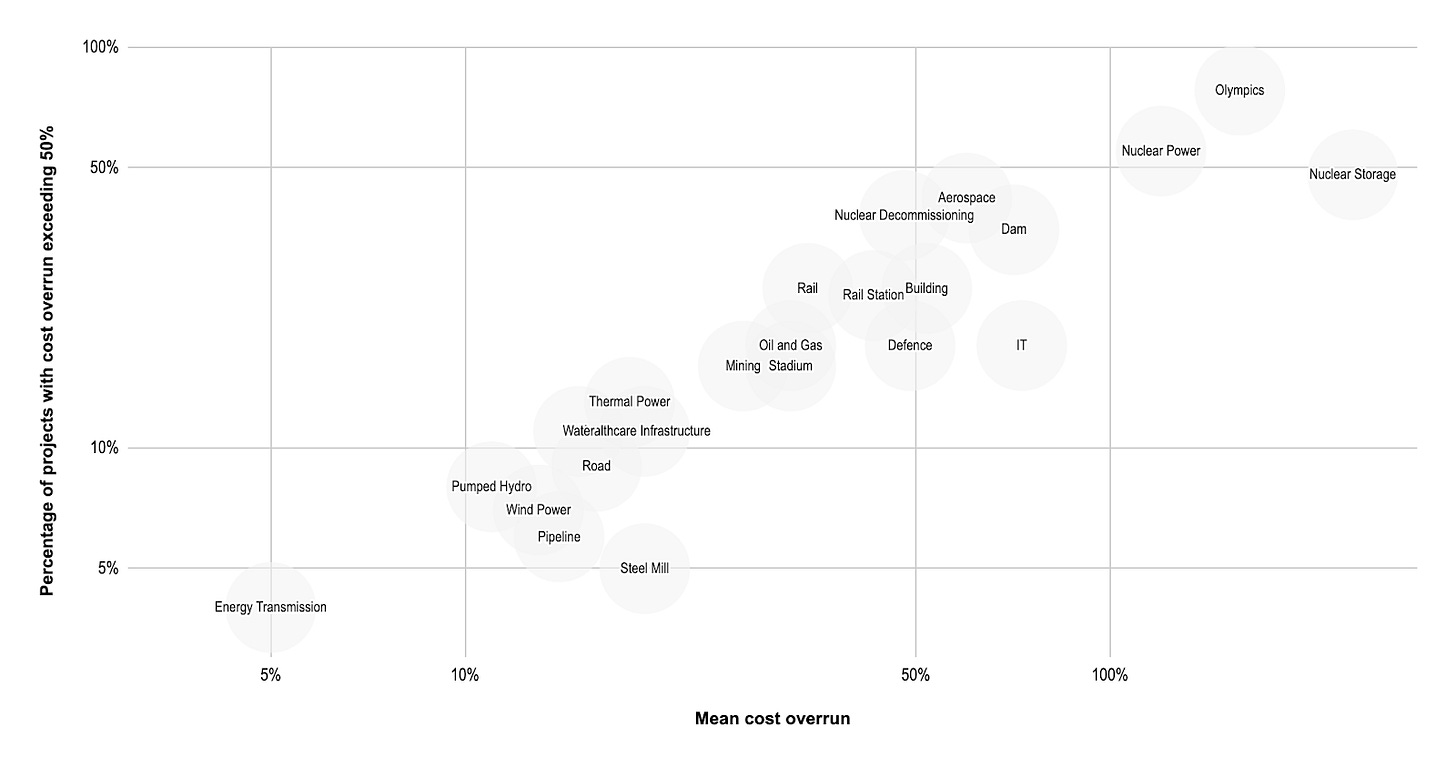

More nuanced, quantitative studies have aimed to build solid evidence to help delivery, particularly on large, expensive projects. As studies from Oxford Global Projects (OGP) have shown, drawing on thousands of case studies and data, most large projects overrun on cost and time, see below. Not well visualised are “black swan” projects, like the Olympics, which have historically overrun sometimes over 400% of budget.5 Naturally, overruns are very clearly linked to more regulated industries.

So why do project managers not simply adjust their project budgets, usually upwards, to be more realistic?

The OGP researchers identify ‘uniqueness bias’: people believe their projects are more unique than they really are. Instead, they encourage their readers to consider their project as less ‘unique’, embedding it within the evidence available. Indeed, the evidence presented is encouraging enough that we listen to it: simplifying the state, particularly in a time of relative peace and security, will be very hard.

Political interest in transformation

Interestingly, debates about wholesale work reorganisation have historically taken place amidst a curious mixture of sociologists, management consultants, industrial activists of both the radical left (e.g. the Communist Party of Great Britain; Socialist Workers’ Party) and right (e.g. British Union of Fascists), and science fiction authors, for example Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry for the Future.

By comparison, and crucially, the parliamentarian centre-right and centre-left have paid much less attention to such organisational or technological topics over the past century and more. This means these themes have rarely featured in political manifestos or indeed government policies.

Interesting experiments or ideas in work organisation tend to manifest in outliers such as Stafford Beer’s experiments with Cybersyn in Chile from 1971-73 or the 1976 Lucas Aerospace Workers’ plan.

An exemplar of a top-down project, Cybersyn was a project implemented by Chile’s socialist Allende government from 1971, augmented by British management consultant Stafford Beer, to use operations research and ‘management cybernetics’ to control Chile’s economy and resources centrally. While initial experiments seemed promising, Pinochet’s violent coup in 1973 effectively shuttered the project.

The 1976 Lucas Aerospace Workers’ plan was drawn up in response to job cuts at the Lucas Aerospace Corporation. In contrast to Cybersyn, the Lucas plan was developed from below — by shop stewards and union leaders. The shop stewards researched and prepared a detailed plan of new product design, workplace reorganisation, and training to simultaneously achieve two goals: i) to stop job cuts by generating new, desirable products and therefore work, and ii) to shift Lucas’ outputs from military equipment to sustainable and socially useful products. While the Lucas plan did not proceed, its bottom-up nature, foresight and attention to detail has prompted a number of documentaries (for example in 1978 and in 2018) and political debates since.

Noted above, there is a reason why these outliers tend to be utopian: execution and implementation are much harder than conception or design.

British reform is tepid compared to American reform

Within the UK, the language of cutting red tape has been popular for some years. For example, under the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government, in 2011 the Prime Minister David Cameron launched a new regulatory system to reduce ‘costly, pointless, and illiberal government red tape’. This involved ‘introducing a new one-in, one-out rule, meaning Ministers have to identify an existing piece of regulation to be scrapped for every new one proposed’. This became known as the ‘Red Tape Challenge’. The Red Tape Challenge involved consultation, and essentially crowdsourcing, challenges to existing regulations from stakeholders. The idea was that ministers would then be summoned to defend their regulations against these challenges. Within several years the government claimed to have removed or abolished thousands of regulations. The Red Tape Challenge appears to have dissipated with the centrality of the Brexit referendum from 2016 onwards.

Contrast this to the US Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), conceptualized in 2024 and implemented in 2025, as a highly apt case study. Having been underway for around three months at the time of writing, DOGE has gained a reputation for chaos, duplicity or even outright failure. For example, consider the reported firing and rapidly rehiring of 300 employees of the US National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which controls the US nuclear weapons stockpile.

However, this interpretation underrates Musk’s risk appetite for organizational experimentation; he clearly believes such experiments reveal essential components versus faulty or inessential ones — no matter how public these apparent ‘failures’ are.

Consider:

The relaunch of social media platform X featuring an interview between Musk and then-presidential candidate Donald Trump, beset with technical difficulties (August 2024)

Experimental SpaceX Starships which disintegrated after launch in January and March 2025.

Moreover, while it has a reputation as simply an aggressive cost-cutting exercise, part of DOGE’s remit also relates to government transparency. A glance at the DOGE.gov website reveals novel new ways of conceptualizing the state at the top level:

Restructuring and headcount reduction (the most reported aspect)

Cancelling projects deemed wasteful

Interrogating state reliance on private consultancies and cancelling contracts

Calculating savings (aggregate and per taxpayer)

Developing an ‘efficiency leaderboard’ of all federal agencies

Transparency of employment by agency including i) years of tenure ii) annual salary and iii) average employee age. (DOGE’s source: US Office of Personnel Management)

An Unconstitutionality Index: the ratio of agency rules to laws passed by congress, per year. (2024 – 18.5:1)

While in aggregate these changes may seem unfamiliar, eccentric, even, most are in fact the culmination of many organizational transparency proposals, or the logical conclusion of existing ones.

At the present moment, when you compare us to our trans-Atlantic partners, you see a distinctive vision of what 2020s efficiency looks like: with a remit across all federal agencies driven by a business elite with a reputation and, to an extent, track record of cost-cutting success. In contrast, the British approach feels very consultative, very admission-based, barely radical, allowing for significant omission when someone gets too close to an interest that someone wishes to protect.

After 100 days of the Trump presidency, observers are now attempting to calculate DOGE’s actual savings. Time will tell if the DOGE’s interventions are successful in terms of achieving long-term cost savings, increased state efficiency, and better value for taxpayers.

A recent study has shown that historically US and UK efforts over the past century were much closer in tone and style, and quite different from DOGE’s current approach. Indeed, whilst most overseas governments and policymakers will reject the tone and pace of DOGE, in fact the reception of what DOGE wants to do has generally been positive, including from centre-left governments such as the UK’s. Labour established the Office for Value for Money in late 2024, and, at the time of writing, Labour Together’s ‘Project Chainsaw’ is gaining traction, with the Prime Minister Keir Starmer and other Labour figures suggesting that while the language may be overheated, necessary change is very real.

Simple mechanisms decrease cognitive load and economic friction

Recently, I read “Designing Simple Mechanisms” by Shengwu Li, which revealed something obvious but profound: you can have completely different outcomes depending on how two mathematically equivalent marketplaces are presented to participants.

A classic illustration of this is found in auction design. Consider the “second-price sealed-bid auction” (SBSPA) conceptualised by economist William Vickrey, each bidder submits a bid privately and simultaneously (to acquire some item of value). The highest bidder wins the item, but the price paid is equal to the second-highest bid.

Imagine you’re participating in such an auction. Depending on how competitive you are, you may immediately start playing mind games against the other bidders. For example, trying to work out their spending power in relation to yours, perhaps bluffing how much you would bid, or trying to form coalitions to underprice the item. Although theory shows that bidding one’s true internal valuation is technically the optimal strategy, this rarely happens in practice when real humans participate in such auctions.

In contrast, consider the dynamic ascending auction. The auctioneer starts by announcing a low initial price for an item, and bidders signal their interest by raising their bids in small increments. At each step, every bidder simply compares the current price to their own private valuation—if the price is below what the item is worth to them, they continue bidding; if it exceeds their valuation, they drop out. The auction continues until only one bidder remains, who then wins the item at the final price. However, this final price is only a fraction more expensive than what the second highest bidder would pay — therefore the two auctions are mathematically equivalent! Except in one version, everyone acts together at a single point in time and in the other, we have a sequential process. Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that in ascending auctions, participants converge on truthful bidding far more reliably than in sealed-bid formats.

The key advantage of the ascending auction is that it makes the optimal strategy transparent. At each increment, bidders need only focus on a single, clear comparison: Is the current price lower than my private value? If yes, keep bidding; if no, withdraw. This simplicity minimizes the room for error and levels the playing field for bidders with varying levels of strategic sophistication. It also enhances trust and transparency because the decision process is visible and intuitive — participants see in real time that deviating from truthful bidding offers no benefit. Economists often refer to such processes as “strategy proof”.6

In a sense, participating in the UK economy is like participating in an SBSPA, we spend huge cognitive effort trying to understand a complex system. Even though the government would prefer people to play fairly and there to be trust between citizens, from a game theory perspective, this is not being encouraged. In today’s complex global economy, adopting simple, transparent rules can help align incentives, reduce errors, and foster a fairer, more robust marketplace.

What does good look like?

Imagine a world in which every key policy can be summarized in a sentence that captures its essential meaning and applies in almost every situation. Such clarity would serve as a common reference point for both citizens and policymakers.

For inspiration, consider Hong Kong wherein corporate profits, personal income and property tax (applied to rental income) are all approximately taxed at a flat ~15% rate above a modest threshold. This system does not recognise citizenship and residence is irrelevant. There is no sales tax (or VAT) and no capital gains tax. It's simple to import and export with the coastal city operating as a free port. Whether you agree with such a policy or not is missing the point: such an approach is incredibly simple. Whilst the form is getting more complex as years go by, it is still only a few pages in length.

Consider yourself a random member of Hong Kong society. Whether rich or poor, there is very little to be gained from trying to game such a system. Many of the micro-optimizations we try in the UK (see types of businesses in the UK), would have no benefit — the tax rate would remain the same. There are also second order benefits: the need for a service economy of tax accountants and lawyers reduces, and other professions can take prominence.

Whilst such a simple worldview can draw criticism — Hong Kong does have a sizable population in poverty (see works in progress piece explaining this) — its taxation system is considered one of the most straightforward systems globally. With such a system in place, there is the aforementioned tendency to make things more complicated over time, for example, the recent move to introduce a top tax bracket (compared to changing the base rate). Whilst this may encourage an ultra-high income individual to game the system, this is still a far cry from the UK.

Some very simple policies

There are some rules and systems that cannot be gamed and when market participants have fewer options available to them, the more likely it becomes to design fair systems. Below, I muse over two areas whereby I believe one can achieve strategy-proof outcomes.7

The astute reader will note that when I refer to numbers X and Y below, one can superimpose political positions onto these. For example, perhaps a left wing position may state that X should be very large, and perhaps a right wing position may state that X should be very small. Here, I’m actually less interested in what the actual numbers should be, but more about making a point about how a mechanism operates.

Universal basic income (UBI) & tax: Imagine every citizen received £X per year from the government and paid a flat Y% of their income (regardless of source). Black markets aside and assuming that UBI covered some minimal quality of life, if one wanted a higher standard of living they would have to earn more (assuming that all other benefits were wrapped into the UBI). Bizarrely, such a motivation is not necessarily true in the UK anymore: there are numerous reports on how increasing the number of hours can lead to a disproportionate reduction in benefits for part time workers.8

Migration: Advanced economies around the world universally agree that some level of migration from both developed and developing countries is desirable. Imagine each year we randomly accept X individuals on humanitarian grounds and Y individuals using some agreed upon cost-benefit analysis.9 By creating two transparent routes for entry, one can move away from political point scoring. Moreover, economic migrants know that they have been selected on some meritocratic basis.

The above was quickly conceived and needs a real economist to sweat the details. However, such a data-driven approach makes it easier to monitor, adjust targets over time, and behaviour becomes more predictable. Regular reviews based on objective metrics help ensure that the policy remains fair and resilient against attempts to exploit any loopholes, making the system more robust and accountable overall.

The difference between British problems and global problems

Many aspects of the above are arguably problems applicable to the whole of the West (or even the whole world), however there are some points whereby the UK suffers from very specific problems.

At a cultural level, we overly reward and ennoble strategic executive roles over operational roles. Historically, this may originate from how we structure the army: we have the officer class who went to university and the “squaddy” who may have dropped out of high school. This manifests as an oversupply of various nontechnical consulting roles with the few technical strategy roles focused almost exclusively on quantitative trading. Outside of finance, this dichotomy between strategy and operations is in direct conflict with most strategies that emerge from an on the ground understanding of specific technical tactical tissues at hand.10

If you follow the Crush Crime initiative, it seems there is a huge backlog in bringing dangerous criminals to trial. Connected to this, the UK’s legal system is widely regarded as one of the world’s most complex due to a unique combination of historical and structural factors. It has evolved over centuries through judge-made common law (precedents) rather than a single written code, leading to a densely layered body of rules. Uniquely, the UK encompasses three different legal jurisdictions within one country – England & Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland – each with its own laws and court system (plus 14 overseas territories, most a hangover from the British Empire). Compounding these factors is an unusually deep court hierarchy: cases can progress through up to four tiers of courts on appeal (from local magistrates’ courts all the way to the Supreme Court). By contrast, most countries lack this degree of jurisdictional complexity and have far fewer court tiers, which is why the UK’s legal framework stands out as exceptionally intricate in global terms.

Lessons from Europe: Finland is committed to simplicity by default

Finland is often studied by other countries for its social welfare, education, gender and, increasingly, defence aspects. However it is also valuable to note its direct and explicit commitment to government simplicity and efficiency. Indeed, the Finns realise definitions are important, as efficiency can be conceived as going beyond cost-effectiveness. To quote the National Audit Office of Finland (Valtiontalouden tarkastusvirasto; VTV):

“Efficiency means on one hand economic efficiency of an authority or the achievement of objectives by using as little resources as possible. On the other hand, it also means flexible and error-free operations of a public or private party. According to the requirement of efficiency, a public party should consider not only its own expenses but also the expenses of other parties.”

The Finnish logic, including why it experimented with UBI for two years, is that policy complexity leads to additional costs for the state and its citizens. Essentially, that simplicity is cheaper for citizens’ taxes and time, and therefore should be a clear goal of state entities. This has helped to ensure the continuance of these principles across successive Finnish governments of many political complexions. A similar rationale exists in Finnish customer protections, in that businesses are expected to provide services and information focusing on the least-informed customer. This in turn reduces the incentive for businesses to provide services requiring their customers employ advisors to help them navigate the customer experience.

In closing

Historically, Britain has prided itself on being the banker for the world — a role that ultimately became untenable as global capital markets evolved. Today, the true sources of wealth lie in land and intellectual property, not in the labyrinthine financial services that once defined our economy. The arguments presented here advocate for a one-size-fits-all, principle-based approaches that might serve as the foundation for a modern British constitution. By embracing radical simplification, the UK can untangle its regulatory web, restore fairness, and re-establish a foundation for genuine, sustainable growth.

If we manage to fix this, looking forward Olson’s insight remains vital: without constant vigilance against the influence of narrow special interests, even sweeping revolutionary reforms risk evolving into new, complex bureaucracies that can stifle long-term economic dynamism.

One may remember so-called “sweetheart deals” concerning the tax bills of various high profile organizations, including Vodafone, GE, Amazon, etc. One could also include aspects of tax avoidance and corruption in this debate. Naturally, such outcomes are only possible due to complex rules.

There’s a question as to whether AI can help us navigate this complexity, which is missing the second part of the argument: complex systems disrupt incentive structures (see later section on simple mechanisms). However, I do not entirely wish to throw out the concept of using technology to improve incentive structures.

See also, the ‘Bermuda Triangle of Talent’.

Because of all of the deaths.

This is in contrast to the striking example of New York’s Empire State Building, still iconic to this day. It opened in 1931, exactly on schedule, at a cost of 17% under budget.

Shengwu’s contribution was to define obviously strategy-proof mechanisms, i.e., “ungameable”.

Disclaimer, not an economist!

I’ve been asked how this is different to negative income tax (NIT). Essentially, here the marginal benefit is constant, i.e., if you earn 25% more than last year, you take home 25% more (excluding the UBI aspect) and pay 25% more tax. With NIT, you require a more complex, less intuitive calculation (i.e., the slope changes). It goes without saying, our proposal is much simpler. Furthermore, NIT still allows for unintended second-order consequences, e.g., tax consultants for hire to structure income from one year to another to maximise NIT benefits.

For example, fiscal impact could include accounting for tax revenue generation after deducting expected costs relating to dependents.

Drawing on my own experience, in drug discovery esoteric technical details frequently inform research strategy. For example, specific types of data availability, feasibility and translation of specific model systems, internal expertise, which then need to fit into a broader commercial strategy.